House vs. Pension – Save early, save sensibly

Technical Article

Publication date:

11 February 2020

Last updated:

25 February 2025

Author(s):

Matthew Yeates

A house can be a significant financial asset, . However, most people don’t realise that with a little planning, their largest financial asset could be their pension. Matthew Yeates, Quantitative Investment Manager talks about saving early and sensibly for later life.

Common misconceptions

Common knowledge can be misleading. When I go to the coffee shop near the office, I’m asked what beans I would prefer for my flat white. Yet, while it is widely believed that coffee comes from 'beans', it actually comes from seeds – we just call them beans because of their appearance.

You sometimes hear that the Great Wall of China is the only human-made object that can be seen from space. However, the Apollo astronauts confirmed that you can't see it from the Moon. In fact, when you look at the Earth from the Moon, all you can see is a sphere of white, blue and a bit of colour – no evidence of humanity at all.

Another widely held belief is that buying a house is the ticket to financial security. But is this true?

It’s certainly true that millennials are struggling to buy houses (due to drinking too many expensive flat whites made with their favourite seeds, no doubt). But should younger people like myself be worried by that fact?

The maths of retirement – time is your friend

A house can be a significant financial asset, especially when people stop working. However, most people don’t realise that with a little planning, their largest financial asset could be their pension – most don’t start saving for their pension early enough as a result.

Time for some maths.

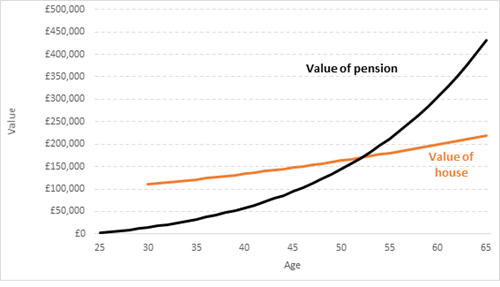

Let’s take a 25 year old, earning 10,000 flat whites a year (or £25,000). Helped by their employer, they save 8% of their salary every year into a pension and invest in a portfolio which should return around 6% a year over the long term. By age 30, they now earn £28,000, and buy a property worth £110,000, just under four times their salary. Well-disciplined with their money, they keep saving that 8% every year.

Fast forward to age 65. With the regular pension contributions and portfolio growth of 6% a year, their pension has grown to £432,000! If we assume the house appreciates in line with inflation at 2%, it would be worth only £220,000. Even appreciating at 3% per year, it would be worth only £310,000 – still over £100,000 short of the pension. That is the power of starting early, and letting time and compounding do the hard work. The conclusions are the same whether you earn £100,000 or £10,000 p.a.

The financial services industry tends to give out the message that saving for retirement is all about quantity – to have a better retirement, the only answer is to save a large amount of cash. Actually, this isn’t necessarily the case, as long as you start early enough.

Start saving early …

We can see this if we change the example a little. Back to my saver. Let’s assume they stop saving into their pension after 20 years, at age 45. Twenty years’ worth of contributions mean that this pot will still go on to reach a respectable £281,000.

But if they wait until 45 to think about their pension, things don’t look so good. Although they’ll be putting away a larger cash sum each month (8% of a higher salary), they will end up with only £130,000 by the time they retire. Their pension is only exposed to growth for 20 years, versus the 40 years for the saver who stopped at 45. So, although the early saver contributed less cash to their pension, they’ve ended up better off than the late-starter.

Unfortunately, many savers in the UK leave saving into their pensions late, often because they’ve focussed on saving for a house, rather than for their future.

For younger generations, the key point is the difference that starting early can make. Of course, this is also relevant to any parents or grandparents who may be thinking of how they can help their children or grandchildren find their financial feet. Even if it’s not explicit financial help, the right advice and good habits can go a long way.

It’s a question of saving smarter, rather than simply saving more. When you are young and your pension pot is smaller than your salary, your savings matter more than your returns. 1% of your salary is more money than 1% growth in your investment.

Saving for a deposit is likely to be the number one priority for many young people. However, if this is at the expense of saving nothing for their pension, they may be doing themselves a disservice.

We all need somewhere to live and the idea of one’s own home can be an emotional aspiration as much as a financial one. Young people already saving into a pension (and their grandparents) shouldn’t be scared, though. They will likely finish up with a much bigger financial asset than those who prioritised buying a property.

… stay invested later

Of course, financial education doesn’t stop at saving! Once you’ve built up a large pension pot, later in life, investment returns and the overall level of risk taken tend to become more important than saving. 1% of investment growth is worth much more on a big pool of savings, so you need to make sure you stay in the market.

The conventional wisdom in finance is that investment pots should automatically start de-risking as people get older and approach retirement. We think that’s as big a misconception as focussing on buying a house… or that coffee comes from beans. Most people approaching retirement can expect to live for 20–25 more years, and should stay invested for as long as possible.

Caption: This chart shows how regular saving into a pension from the age of 25 could result in much greater wealth at retirement than buying a house at the age of 30.

Source: 7IM

This document is believed to be accurate but is not intended as a basis of knowledge upon which advice can be given. Neither the author (personal or corporate), the CII group, local institute or Society, or any of the officers or employees of those organisations accept any responsibility for any loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of the data or opinions included in this material. Opinions expressed are those of the author or authors and not necessarily those of the CII group, local institutes, or Societies.